Early Printing Efforts

During the reign of Mehmed II (1451 – 1481), the Ottomans were aware of the printing press, but they did not adopt it. The reasons for this reluctance are debated among scholars. Some argue that it was due to the fear of economic impact on scribes and copyists who were privileged in Ottoman society. Others believe it was a pragmatic decision by Ottoman authorities. The exact timing of the first printing house and book in the Ottoman Empire is unclear, but it’s known that books in Arabic script couldn’t be printed within Ottoman borders for a long time.

Role of Calligraphers and Scribes

There was an estimated 90,000 calligraphers in the Ottoman Empire during the 18th century, and they resisted the establishment of printing houses, fearing job loss. However, recent research leans towards a more pragmatic explanation, suggesting that political and economic factors influenced the Ottoman Empire’s decision regarding printing.

Printing by Jewish Communities

Jewish immigrants played a role in early printing in the Ottoman Empire. The first book printed was likely in Hebrew between 1488 and 1493. Printing houses were established in various Ottoman cities by Jewish communities, including Thessaloniki, Aleppo, Damascus, and Izmir.

Printing among Armenians and Greeks

Armenians and Greeks also established printing houses. The first Armenian-printed book was produced in Venice in 1512, and the first Armenian printing house within the empire was founded in 1677. The first Greek printing house was established in 1627, but it faced challenges, including attacks by the Janissaries.

Printing in Arabic/Ottoman Turkish

The earliest books with Arabic script were printed outside the Ottoman Empire, such as the first book with Arabic letters in Italy in 1514. The first Quran using Arabic typeface was printed in Italy during 1537 or 1538. The Ottomans later allowed printed books to be sold within the empire.Printing by European Diplomats

Ambassador François Savary de Brèves established a printing press in the French Embassy building in Istanbul in 1587. He published a peace treaty in both French and Turkish in 1615, considered by some as the first full-text publication in Turkish.

The Complex Reasons for Reluctance

The Ottoman Empire’s reluctance towards the printing press had multifaceted reasons. Some suggest it was due to religious concerns about the Quran, while others argue it was political, aiming to avoid conflicts among the diverse “millets.” Socio-cultural factors, such as the value placed on hand-copied books, also played a role. Ottoman scribes had a moral duty to transcribe the holy text beautifully, which couldn’t be replicated by printing. Additionally, the existing bureaucratic system and the absence of widespread religious debates contributed to the slow adoption of printing technology in the Muslim world.

In summary, the Ottoman Empire’s hesitation to embrace the printing press was influenced by economic, political, and cultural factors, making it a complex and multifaceted historical phenomenon.

Ibrahim Müteferrika and the Ottoman Printing House

Ibrahim Müteferrika was instrumental in introducing the printing press to the Ottoman Empire in the early 18th century. His journey to France as an ambassador marked a significant shift in Ottoman engagement with the West. Upon his return, his son, Yirmisekiz Çelebizade Mehmed Said Efendi, played a role in establishing the first printing house.

Ibrahim Müteferrika was a Hungarian who converted to Islam and had a mysterious background. He may have been a Calvinist theology student before being captured by the Ottomans during an uprising against the Habsburgs. He served in various capacities within the Ottoman Empire, including diplomatic missions and as a translator.

In 1719, Müteferrika obtained permission to establish a printing house. His first publication was “Vankulu Lugatı,” a Turkish translation of an Arabic dictionary. He went on to publish seventeen books before his death in 1745. These works covered a range of topics, including history, language, geography, and science, reflecting Müteferrika’s utilitarian philosophy.

The printing house continued under different managers after Müteferrika’s death, with Kadı Ibrahim Efendi and Raşid Efendi briefly overseeing its operations. In 1797, the printing press was transferred to the Imperial School of Military Engineering and produced course materials until 1831.

Ibrahim Müteferrika’s pioneering efforts in printing played a crucial role in modernizing Ottoman intellectual life and facilitating the dissemination of knowledge.

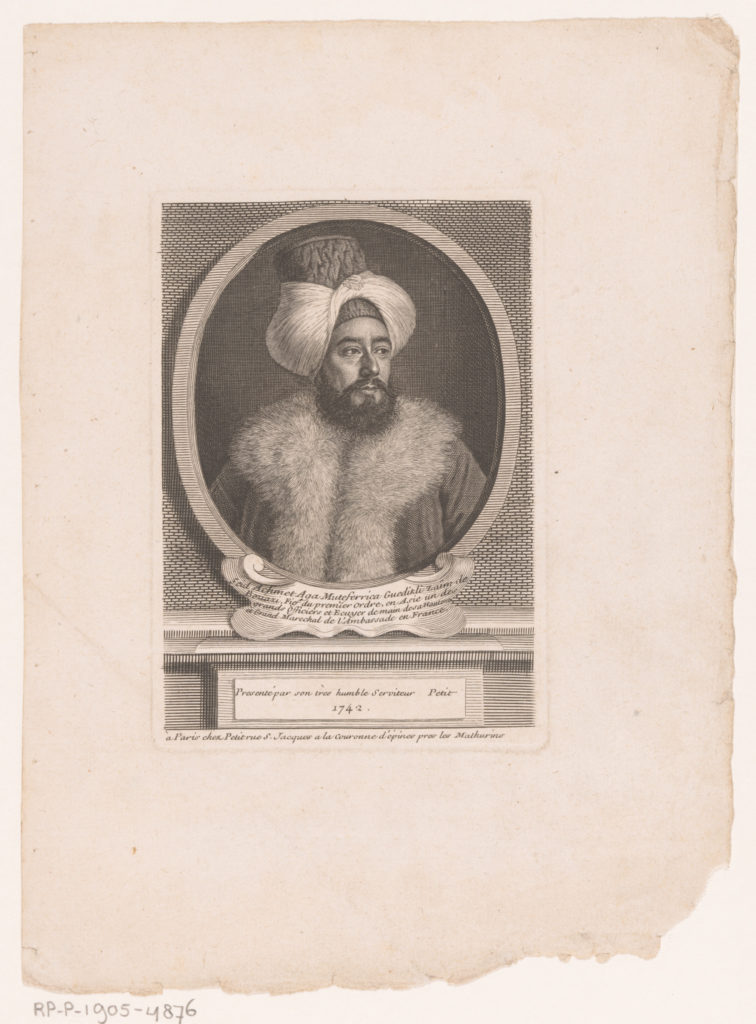

Ibrahim Müteferrika, the first Ottoman Turkish Printer

Portrait of Ibrahim Muteferrika.

by Gille Edme Petit, print maker, Frans (1694–1760)

Origin: Paris. Date: 1742.

Object ID: RP-P-1905-4876.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

French Consulate Printing House in the Ottoman Empire

During the 15th and 16th centuries, as Europe saw the rapid spread of the printing press, the Ottoman Empire reached its zenith in terms of political and military power. It formed diplomatic ties with France to counterbalance other European powers like the Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires through agreements known as capitulations. Over time, these agreements evolved, laying the groundwork for later free trade deals.

Initially, the Ottomans lagged behind in adopting European cultural and scientific advancements. However, as conflicts subsided, they began transferring military knowledge and technology from European allies, with France playing a crucial role, especially after the Ottoman Empire suffered territorial losses to the Habsburgs in the late 17th and 18th centuries.

In 1785, the French Embassy received permission to establish its own printing house in the Ottoman Empire. They imported printing machines and materials, including Arabic/Ottoman Turkish typefaces. This marked the Ottomans’ growing awareness of European advancements, coinciding with military defeats against Western powers. The Ottomans started seeking technical expertise from abroad, expanding relations with France beyond commerce.

The French Embassy’s printing house initially focused on publishing military-related books in Turkish. Notable publications included works on fortification and naval warfare. Additionally, they published a Turkish grammar book. As the French Revolution unfolded, they printed materials on civil rights and republicanism. A periodic bulletin called “Bulletin de Nouvelles” served as a communication tool, later replaced by “Gazette Française de Constantinople.” Tensions between France and the Ottoman Empire led to arrests and temporary closures, ultimately ending the publication of these newspapers.

Amid these changes, Sultan Selim III initiated administrative and educational reforms. The Matbaa-i Amire, the first official printing house, was established. Modern-style educational materials were printed for Western-style schools. Despite these efforts, the Ottomans struggled to comprehend the profound social changes in Western societies during Selim III’s reign, particularly the French Revolution’s democratic principles and ideas of freedom and equality. Instead, they often perceived it as a form of plundering and looting, missing the underlying intellectual movements.

These developments marked a period of change and adaptation in the Ottoman Empire as it sought to modernize and engage with the Western world.

Henri Cayol: The First Lithographer of Istanbul

Henri Cayol (1805 – 1865) introduced lithography to the Ottoman Empire. Despite his background in law, Cayol’s passion for painting and manuscripts, coupled with a natural talent for lithography, drew him to this art form. His journey to the East, accompanied by his nephew Jacques Cayol, who also possessed skills in stone engraving, further nurtured his interest. In 1831, at the age of twenty-six, Cayol decided to settle in Istanbul, where he quickly learned Turkish with the help of a tutor. He began advocating for the benefits of stone engraving to Ottoman officials, emphasizing its ability to preserve the beauty of Ottoman calligraphy.

With support from Koca Hüsrev Pasha, the Serasker (army commander vizier) at the time, who saw practical uses for stone engraving in army training, Cayol obtained permission to establish a workshop. The first published work in this field, “Nuhbetü’t-ta’lim” (Battalion Training), was released in 1831, containing seventy-nine training illustrations. Sultan Mahmud II recognized Cayol’s contributions and provided him with a house, a monthly salary, and provisions. While working under government supervision, Cayol also operated his own printing house, publishing military-oriented books with illustrations, all using the stone engraving technique.

In 1836, Cayol established his independent printing house with the permission of Sultan Mahmud II. He published various works, including French grammars and dictionaries, some of the first designed for Turks. Over time, he published in Greek, Armenian, and French scripts. Cayol also served as the editor and publisher of the “Journal Asiatique de Constantinople,” which began in 1852.

In 1852, a fire destroyed Cayol’s printing house and many valuable documents and manuscripts. Despite this setback, he rebuilt it near the French embassy building, purchasing new equipment from Paris in 1855. Henri Cayol passed away during the cholera epidemic of 1865, leaving behind a significant collection of manuscripts, the catalog of which was published posthumously.

After Cayol’s death, Antoine Zellich, his disciple, briefly managed his printing house before establishing his own workshop in 1869. This tradition continued, with Antoine Zellich’s son, Grégorie Zellich, commemorating the 100th anniversary of lithography’s introduction in Turkey in 1895 with a treatise. Over time, government-owned lithography printing houses were established, and civilian entrepreneurs opened stone engraving workshops in Istanbul, numbering more than thirty by the 1850s.

19th Century Ottoman Modernization and Printing

In the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire underwent a modernization and westernization movement initiated by Sultan Mahmud II. Despite challenges like territorial losses and national independence movements, the Ottomans employed a balancing policy involving England, France, Russia, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. This policy, known as the “Eastern Question,” aimed to shift power balances within the empire. Economic and political changes ensued, driven by free trade agreements.

Western powers influenced the empire by supporting the rights of ethnic and religious groups. To preempt external intervention, the Ottomans instituted reforms like the Tanzimat Edict (1839) and Islahat Edict (1856). Calls for a constitution and parliament grew, particularly among the Young Turks.

In response, the Ottoman Empire proclaimed its first constitution, the Kanun-i Esasi, in 1876, establishing a parliament. However, Sultan Abdulhamid II disbanded it in 1877, starting his autocratic rule, “İstibdat,” for three decades.

State and Private Printing Houses

In 1831, the Ottomans inaugurated the first state printing house, Takvimhane-i Âmire, during Mahmud II’s rule. This move aimed to produce books for modern schools, official newspapers, and essential documentation for bureaucratic reorganization (Başaran, 2019).

Exclusive printing rights were granted to the state printing house between 1831 and 1839, but unauthorized private printing houses emerged. In 1857, individuals were allowed to establish printing houses with inspection mechanisms. The Tanzimat Fermanı (Imperial Edict of Reorganization) in 1839 marked the start of the Tanzimat Era and the liberalization of book production.

Private printing houses surged after 1839, leading to challenges at Takvimhane. Sahafs, who were traditional booksellers, began opening their printing houses, diversifying the book market.

Non-Muslim book printers became prominent in the latter half of the 19th century, publishing various works. Iranian printers and booksellers, known as Acem, also played a role in printing and distributing Turkish books. These changes transformed the book market.

Book peddlers, a precursor to modern bookstores, emerged, requiring regulations. In 1895, specific rules were introduced, defining the roles and limitations of book peddlers in book distribution.

- Adıvar, A. (1982). Osmanlı Türklerinde Ilim. Remzi Kitabevi.

- Babinger, F. (2004). Müteferrika ve Osmanlı Matbaası. Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları.

- Başaran, A. (2019). The Ottoman Printing Enterprise: Legalization, Agency and Networks, 1831-1863. Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

- Başaran, A. (2023). Reconsidering the Role of Ulema and Scribal Actors in the Ottoman Transition from Manuscript tp the Printed Medium. Disiplinlerarası Çalışmalar Dergisi. Vol.29 No. 54. 73-121.

- Baysal, J. (1968). Müteferrika’dan Birinci Meşrutiyete Kadar Osmanlı Türklerinin Bastıkları Kitaplar. Edebiyat Fakültesi Basımevi.

- Berkes, N. (1973). Türkiye’de Çağdaşlaşma. Bilgi Yayınevi.

- Beydilli, K. (2015). Istanbul Matbaaları (1453-1839). Antik Çağ’dan 21. Yüzyıla Büyük Istanbul Tarihi. Vol. 7, 553-577.

- De Young, G. (2012). Further Adventures of the Rome 1594 Arabic Recadtion of Euclid’s Elements. Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 66(3), 265-294.

- Dığıroğlu, F., & Yıldız, G. (2018). Osmanlı Devleti’nin Şii Neşriyata Bakışı ve Acem Kitapçılar. Müteferrika, 54, 117-134.

- Erünsal, İ. E. (2013). Osmanlılarda Sahaflık ve Sahaflar. Timaş Yayınları.

- Faroqhi, S. (1999). Approaching Ottoman History. Cambridge University Press.

- Galanti, Avram (1995). Türkler ve Yahudiler. Gözlem Yayınları.

- Gerçek, S. N. (2019). Matbuat Tarihi. Mustafa Kirenci (Ed.). Büyüyenay Yayınları.

- Hitti, P.K. (2001). The first book printed in Arabic. The Princeton Library Chronicle. V.4.1. 5-9.

- Kabacalı, A. (1979). Türk Yayın Tarihi. Cem Yayınevi.

- Kahraman, A. (2011). Taş Basması. TDV Islam Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 40, 144-145

- Levy-Aksu N., Georgeon F. (2019). The Young Turk Revolution and the Ottoman Empire.

- Malhasyan, S., & İncidüzen, A. (2012). Baskı ve Harf: Ermeni Matbaacılık Tarihi. Birzamanlar Yayıncılık.

- Neumann, C. K. (2019). Three Modes of Reading: Writing and Reading Books in Early Modern Ottoman Society. Lingua Franca, Vol. 5.

- Pektaş, N. (2014). The First Greek Printing Press in Constantinople (1625-1628). Royal Holloway, University of London.

- Pektaş, N. (2015). The Beginnings of Printing in the Ottoman Capital: Book Production and Circulation in Early Modern Istanbul. Osmanlı Bilimi Araştırmaları, 16, 3-32.

- Sabev, O. (2016). Ibrahim Müteferrika ya da Ilk Osmanlı Matbaa Serüveni. Yeditepe Yayınevi.

- Schwartz, K. (2017). Did Ottoman Sultans Ban Printing. Book History. 20, 1-39.

- Serçe, E. (1997). Seyyar Kitapçılar Nizamnamesi. Kebikeç. 5, 9-16.

- Strauss, J. (1999). Livre français d’Istanbul (1730-1908). Livres et lecture dans le monde ottoman. Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée. Série histoire. Cahors. 277-301.

- Timur, T. (1997). Osmanlı Çalışmaları. İmge Kitabevi.

- Toderini, G. (1990). Ibrahim Müteferrika ve Türk Matbaacılığı. Tifdruk Matbaacılık.

- Watson, W. J. (1968). Ibrahim Müteferriḳa and Turkish Incunabula. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 88(3), 435-441.